Behind the Scenes at Public Broadcasting’s Learning Efforts

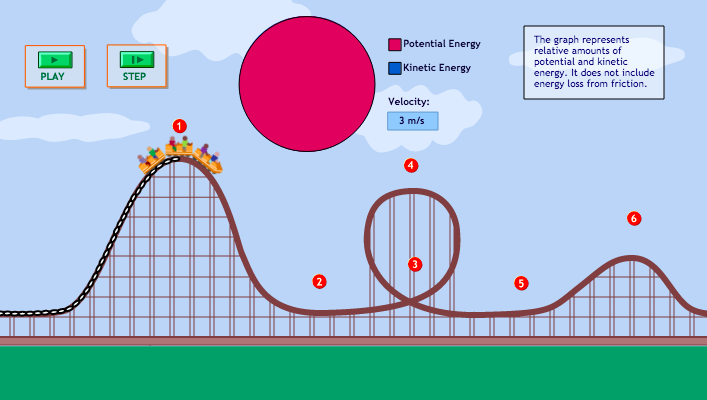

When science teachers try to get their students to understand the physics of potential and kinetic energy, there’s one place thousands of them turn: To the roller coaster videos on PBS Learning Media.

They are some of the site’s most popular resources, said Sara Schapiro, PBS vice president of education. Kinetic energy propels the cars to whiz down the track; potential energy has them groaning up to the next summit.

So how is a teacher allowed to use videos like this or the approximately 100,000 available public media educational resources, asked one viewer recently? Simple: It’s all free to use (unless you’re buying an entire DVD). You are just not allowed to duplicate it, alter it, put it on a website or make money off it.

When fans think of public television, they think of “Masterpiece,” “FRONTLINE,” or the “PBS NewsHour.” When parents think of public TV, they may think first of “Sesame Street,” “Wild Kratts” and other programs on PBS Kids, which help teach young children about numbers, letters, science and natural history.

But when teachers think of public television, nearly one third of the nation’s 3.2 million teachers come to PBS LearningMedia.org each month to access the videos, interactive exercises, lesson plans, student work zones – and even state standards – embedded in the platform, Schapiro said. Resources are searchable by grade and topic.

“Some come back four to five times a month,” she said. “They are super users. We’re seeing more and more of those as classrooms become more and more dependent on media.” Some don’t start out heading for the PBS site, but find it in the top results of a Google search for a particular resource.

There are videos and other tools to teach about everything from earthquakes to green architecture, from geothermal power to electric cars.

In fact, there are so many resources that Schapiro’s team is now culling through and and will soon eliminate some 30,000 or more outdated items.

But, as times change, so do the challenges to public media’s learning initiatives. More states are moving to universal pre-K, amping up demand for early childhood learning resources for 3- and 4-year-olds. Fewer people are buying DVDs, or even own a DVD player any more, so sales of PBS’s educational DVDs have shrunk. Rights to content created by the musicians, producers, actors and others have gotten increasingly complicated as creative works now have additional afterlives on streaming services. Generally, these artists promise to carve out pieces of educational content from their programs in return for receiving public media production funding.

And YouTube has emerged as a place where 81 percent of all U.S. adults with children 11 or younger let their kids watch content; 34 percent say their kids watch YouTube videos regularly, according to a recent Pew Research Center study.

“We recognize that this is happening,” said Michael Fragale, CPB vice president for educational programming and services. “We recognize we have to be in the places where kids are.”

PBS KIDS, which houses children’s public television programming, now has its own YouTube channel, which streams nearly 1,700 pieces of content for some 508,000 subscribers.

But two-thirds of YouTube users say they’ve had negative experiences, reporting false content or troubling behaviors.

That’s where public media has a leg up. While the FCC currently requires commercial broadcasters to air at least three hours of educational television per week, PBS far exceeds that; educational television is part of the core mission of public television. “The PBS brand is so valued by educators and parents,” said Debra Sanchez, CPB’s senior vice president, education and children’s content.

What makes for a good children’s program? “It’s a magical combination of good curriculum, funny and engaging content, good characters – and music is really important,” Fragale said. While STEM (science, technology, education and mathematics) literacy is a key ingredient, programs for young children, in addition to offering humor, also try to instill “this idea of self-regulation,” helping them manage social-emotional behavior, he said.

To provide all of this, CPB takes a few million dollars out of its annual appropriation from Congress. It also has received more than $19 million a year from the U.S. Department of Education from the mist recent five-year Ready To Learn grant, awarded in 2015, to focus on science and literacy learning, especially for disadvantaged children and families. Adding to that, PBS covers educational learning costs out of its operating budget. And local public television (and some radio stations) raise money to cover their own learning initiatives.

Consider, for instance, when Georgia couldn’t afford new history textbooks, Georgia Public Broadcasting created digital history books for students in the state. Idaho Public Television makes available mandatory history instruction for all grades online.

Public media not only focuses on learners, it focuses on teachers, too. KQED Public Television in San Francisco offers pre-K to 12 teachers certificates in media literacy, attesting to skills in teaching such things as finding information online, understanding copyright and fair use, or engaging in video storytelling.

Recently, CPB empowered 50 local public broadcasters to come up with innovative education pilot projects, awarding each $10,000 from a $500,000 grant. The ideas weren’t all for young children, Fragale said. They included using virtual reality technology, involving young people in media labs and building worker skills.

Another opportunity at the forefront is podcasting. “There are different ways we can reach kids, either through video content or audio content. How do we use podcasting? We know with podcasting that there is joint behavior happening .… You can create something parents and kids will listen to,” Sanchez said.

“There are huge changes in how people are using media in general and huge changes in how people are learning in general,” she noted. It makes little sense to encourage parents to read to their children for 20 minutes every day if they don’t have 20 minutes a day to do that, Sanchez and Fragale point out.

“We are optimistic,” Fragale said, “that our systems in public media will be positioned to meet that challenge.”

You can subscribe to CPB Ombudsman Reports at https://www.cpb.org/subscribe